|

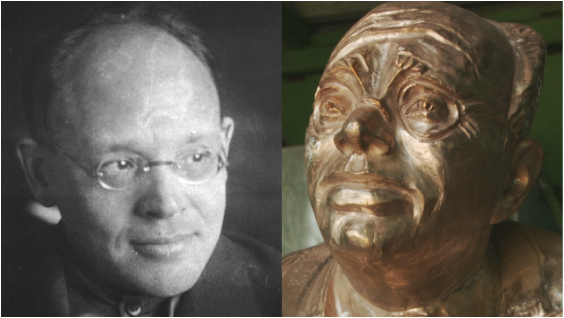

Isaac Emmanuilovich Babel

born July 13, 1894 , Odessa, Ukraine, Russian Empire executed January 15, 1940, Moscow, Russia, U.S.S.R. Isaac Babel was a Russian short-story writer famous for his story cycle Red Cavalry (1926) about the Civil War (1918-21), as well as stories about Jewish gangsters (Tales of Odessa, 1921-31) and a middle-class Jewish boyhood in Odessa under the old regime (Story of My Dovecote, 1926). He combined in his prose aphoristic the brevity with the stylistic extravagance of modernist verse and had a significant influence on the genre of short story. Translated into many languages, his works have for decades exemplified the achievement of Russia’s literary avant-garde as well as the dilemmas faced by a modern intellectual, a Russian and a Jew, caught in the swell of a violent social revolution. Odessa, where Babel was born to a typical middle-class Jewish family, was his chief inspiration. Known for their secularism and cultural vibrancy, the Jews of this most cosmopolitan city in the Pale of Settlement made up a third of its population distributed across the city’s entire social spectrum. Although Babel’s parents were subject to the anti-Jewish policies of the old regime, their values were shaped by the opportunities offered by Russia’s modernization. The family language was Russian (Babel was taught to read by his mother), and Babel’s father, a small but increasingly successful businessman, did his best to give his children, along with instruction in Judaism and Hebrew, a full-fledged modern Russian education, including foreign languages and, typical for Odessa, the classical violin. Babel’s first attempts at prose (none survived) were in French, the fact he attributed to his French-born teacher as well as his familiarity with Odessa’s French expatriate community. After graduating from Nicholas I Commercial School in 1911, Babel went on to study economics and business at the Kiev Commercial Institute, completing it in 1916. He then enrolled in the faculty of law at St. Petersburg’s liberal Psycho-Neurological Institute and proceeded to launch his career as a reporter and short story writer. Although the first published story dates back to 1913, he insisted on having been “discovered” by Maxim Gorky, the most famous Russian writer at the time, whose friendship with and patronage of Babel, beginning with the publication of Babel’s stories in Letopis in 1916, continued until Gorky’s death in 1936. Consonant with Babel’s background, his early stories explored the gritty middle-class world of a modern Russian city whose inhabitants often operated at, or over, the boundary of propriety and law: a small-time Jewish merchant moving in with a prostitute to avoid deportation ("Elya Isakovich and Margarita Prokofyevna”); a desperate gymnasium girl seduced by a boarder and trying to induce an abortion (“Mama, Rimma, and Alla”); a young writer watching through a peep hole the goings on in a house of ill repute (“Through a Peephole”). It was easy for Babel to take to heart Gorky’s injunction to him “to apprentice among the people.” In the manner of Gorky and Guy de Maupassant, Babel took a keen interest in people living by their wits, small-time operators, Bohemians, and members of the oldest profession, whose business he ironically juxtaposed with that of a modern litterateur (“My First Fee,” 1922). Unlike his predecessors, he tended to see them, not so much as victims of rapid change, as resourceful characters putting capitalism and urbanization to their own use. This sanguine outlook found expression in his youthful manifesto (“My Notes: Odessa,”1916) in which Babel predicted the imminent arrival in Russia of a new “literary Messiah,” a new Gorky. This author was to deliver classical Russian literature from its moody, Northern cast and replace it with the sunshine-bathed cosmopolitan zest of the empire’s multi-ethnic South-West. Babel’s career may be seen as an attempt to fulfill this prophecy. After the fall of the old regime in 1917, Babel spent the summer and autumn as a volunteer at the Rumanian front (not far from his native Odessa), later on journeying, at a great risk to himself, back to Petrograd (now St. Petersburg). Without means of subsistence, he was recruited by the Cheka to serve as an intepreter in its foreign intelligence department – a career he soon combined with that of a reporter writing sketches critical of the new regime for Gorky’s anti-Bolshevik newspaper Novaya zhizn (New Life, shut down in July, 1918). In 1919, after a brief stint in the Red Army and a food requisitioning battalion, he returned to Odessa to work for a state publishing house. There he married Eugenia Gronfein, an artist and an old friend from his student days in Kiev. Soon afterwards, assuming a Russian name, Kiril Lyutov, Babel took part in the Russo-Polish war of 1920 as a reporter for Budenny’s Red Cavalryman newspaper, at times serving on the army headquarters staff. Much of the fighting took place in the ethnically diverse borderlands between Poland and Ukraine, a region known for its old Jewish communities. Decimated in the crossfire of WWI, they were now victimized by the two sides in the Russo-Polish conflict. Babel’s experience during this campaign, recorded in a diary, forms the basis for the stories of Red Cavalry. Babel began to work on this material in earnest after he had completed in 1921-23 the core of his Tales of Odessa, a set of Rabelaisian stories about a colorful Jewish gangster Benya Krik and a subtle allegory of Babel’s own (that of an enterprising Jewish writer from Odessa) raid on Russian literature (the story “How It Was Done In Odessa”). The Tales are narrated by a bookish young man – “with spectacles on his nose and autumn in his heart.” He is fascinated by the violent energy and unabashed sexuality of Benya Krik, a Jew “who could spend the night with a Russian woman and a Russian woman would be satisfied.” In these stories, Babel found his unique narrative persona and voice. They inform his oeuvre in its entirety and can sometimes be recognized in the works of the post-WWII American writers exploring Jewish-American life. Red Cavalry’s short stories and vignettes form a unit, similar to a novel, thanks to the character of the narrator Kirill Lyutov. He shares many qualities with the chronicler of The Talesof Odessa (just as the Odessa gangsters get transposed onto Budenny’s cavalrymen), but he evolves between the opening of Red Cavalry and its end. Babel uses this narrator as a device to probe the uneasy confluence of bookish intellectuals and a violent revolution. Sympathetic to the cause of a world revolution, Lyutov finds it hard to reconcile its lofty ends with the immense brutality of means – Budenny’s motley Cossack army which possesses as much instinct for raw social justice as for marauding, pogroms, and rape. This paradox remains unresolved, except ironically on the aesthetic plane, as Lyutov professes his admiration for the will, directness, and vitality of the Cossacks – these cousins to Nietzsche’s blonde Bestie doing the bidding of the Bolshevik regime. For many leftist intellectuals in Russia and the West, Red Cavalry embodied the moral ambiguity of the revolution, its abhorrent brutality overshadowed by an irresistible desire to see ideas unleash and animate the people, a force akin to life itself. Classified as a fellow-traveler, Babel enjoyed an enthusiastic critical response in Soviet Russia. Occasional condemnation, notably Semyon Budenny’s attacks on him in 1924 and 1928, countered by Gorky, stung Babel but also burnished his fame. In 1925, Babel began publishing a series of semi-autobiographical stories in which his familiar narrator was implicitly summoned to “recall” his early years. Presented as part of a book about his boyhood and dedicated to Gorky, the seminal “Story of My Dovecote” and “First Love” (1925) suggest that Babel conceived of his oeuvre as a set of consecutive autobiographical cycles, not unlike Gorky’s trilogy, and he continued to add to it throughout the 1930s. In them, Babel successfully established a new genre of a quasi-autobiographical story about a middle- class Jewish boy, who is tested in and shaped by a complex of opposing cultural forces: opportunities opening up for Jews in the modernizing gentile world and its anti-Jewish prejudice; the parental pressure to succeed and their simultaneous recoil against secularization and assimilation; and finally the confusion of sexual codes articulating the clash between the more traditional Jewish family and the modern non-Jewish world outside. Soviet culture’s sharp turn toward socialist construction and conformity beginning in 1929 threatened to marginalize Babel. Of the several stories he wrote about the collectivization of agriculture (1929-30), two have survived, and only one was published in his lifetime (“Gapa Guzhva,” 1931). Raw and powerful in the manner of Red Cavalry, they stood out from contemporary Soviet prose and did not bode well for Babel’s future in the Stalinist canon (Stalin apparently questioned Babel’s loyalty). From early 1930s on, Babel’s published literary output turns into a trickle: a few short stories and one play. Like some of the other writers of his generation, Babel began writing for the screen in the 1920s, using this opportunity both as a creative outlet and a source of livelihood to supplement meager literary income. A friend and frequent collaborator of Sergey Eisenstein, he was a prominent screen writer and master of film dialogue, but he was also known for notable misfortunes when it came to dealing with Soviet film authorities. The 1927 film, Benya Krik, based on his screen play, was banned after its release. In a similar manner, his 1936-37 collaboration with Sergey Eisenstein on the film Bezhin Meadow (about a young communist boy, Pavlik Morozov, murdered by his retrograde peasant father) was officially vilified for its “formalism” and banned in post-production, its stock destroyed. Yet many of the films of the 1920s and 1930s were based on Babel’s scripts and dialogue. Babel’s sole attempt on the theater stage was his play Sunset (1927). Based on the jolly gangster Tales, it ends with a grim vision of the carnivalesque Odessa underworld transforming itself into a capitalist corporation. Although the 1928 Moscow production of play failed, its run on the provincial stage in 1927-28 – in Kiev, Minsk (in Yiddish), and Odessa, where it played simultaneously in two theaters, Russian and Ukrainian – was an unqualified success. His second play, Maria (1935), announced ostensibly as an opening part of a trilogy, was published but not staged in his lifetime. A member of the Soviet cultural elite, Babel lived abroad for prolonged periods of time in 1927-28, 1932-33, and briefly in 1935. His mother and sister emigrated to Belgium early in 1925, followed shortly thereafter by Babel’s wife, who settled in Paris and bore their daughter there in 1929. Abroad Babel maintained a wide circle of friends and acquaintances among the émigrés as well as Soviet expatriates, most notable Ilya Ehrenburg. He was on friendly terms with Andre Malraux, a famous writer and leader of the anti-fascist left, who took a keen interest in the Soviet Union. Babel hosted Malraux in Moscow during the First Congress of Soviet Writers, a defining moment for Soviet culture in the 1930s. In his speech at the Congress, Babel referred to himself as a practitioner of “the genre of literary silence” but also as one whose creative “gestation was more akin to that of an elephant than a rabbit.” This promise to bring forth a work comparable to Red Cavalry and failure to live up to it could be and was interpreted as a refusal to celebrate Soviet achievement under Stalin, a must for artists favored by the regime. The Great Terror swept away many of Babel’s friends in the military, security, party, and cultural elite, finally reaching Babel himself on May 16, 1939. He had by then started another family in Russia and was father to another daughter, two-year-old Lydia. He was arrested in his country house in the writers village, Peredelkino, where he was then preparing for publication a collection of stories, some new. Accused of espionage and terrorist conspiracy, he was convicted and shot eight months later. He was cleared posthumously of all charges in 1954, but all of his unpublished works, drafts, notebooks, and other papers, confiscated during the arrest, disappeared with trace in the Lubyanka archives. Babel’s literary rehabilitation began in 1957, when a collection of his stories and plays, with a forward by Ilya Ehrenburg, appeared in the Soviet Union. Two years earlier, a notable American edition, with the introduction by Lionel Trilling, became the foundation of the Babel revival in the United States. Gregory Freidin © 2002 Bibliography • Isaac Babel’s Selected Writings. A Norton Critical Edition of Letters, Contemporary Views, Criticism, Scholarship, and Chronology. Trans. Peter Constantine. Ed. Gregory Freidin, with an intro., annot., trans. of the memoirs and critical reception, a critical essay, and chronology (New York: W. W. Norton, 2010). • Isaac Babel, 1920 Diary, ed., transl. and with an intro. by Carol Avins. New Haven, 1995. • Isaac Babel: The Lonely Years, 1925-1939: Unpublished Stories and Private Correspondence. Transl. by Andrew R. MacAndrew and Max Hayward; ed., and with an intro. Nathalie Babel. (Boston, 1994). • Freidin, G., ed. & contrib., The Enigma of Isaac Babel: Biography, Hisotry Context. Stanford University Press, 2009. • Isaac Babel (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom. NY, 1987. |